Velma Morrison, A Woman Worth Her Salt at St. Gertrude's

"A man's worth is counted in the things he creates for the betterment of man." Harry Morrison. So is a woman's.

When I moved to Idaho in 2011 I had no idea who Harry Morrison was. Over the last twelve years I’d heard the Morrison name in Boise (Ann Morrison Park, Morrison-Knudsen, Velma Morrison, and more) but I never wondered who he was. This morning when I got into the elevator in St. Gertrude’s Monastery to ride from the first to the fifth floor I did. A small brass plate inside says, “Gifted by the Harry W. Morrison Foundation.”

“Well, God bless Harry W. Morrison, his children, and his foundation,” I said aloud and meant it. Not having to walk up stairs here is a huge blessing. If I had to walk up and down them multiple times every day for thirty days, I could not be here. I imagine the same is true for most of the sisters. At the time I had no idea that it was actually his second wife Velma who was responsible for the gift.

I’m almost a week into my 30-day residency at St. Gertrude’s, a stately old Benedictine Monastery near Cottonwood, Idaho. Built from rock found on the property, the Monastery with its turrets is a castle-like building overlooking the glorious Camas Prairie. When the skies are clear, from my fifth floor room, I can see the Salmon River Canyon in the distance.

The wing where I’m staying is for residency and other visitors and the nuns live below us on the third and fourth floors. A number of the nuns are elderly. The youngest is 62. Joining the Benedictine community, it seems, is a life-long commitment. In recent months at least three nuns have passed on, one the former prioress (the nun in charge) and one whose funeral I’ll attend this morning.

Time does not appear to be on the side of some of the nuns in this community: one I met has been here for 61 years, and I was told that 100 nuns lived here 50 years ago. Now there are fewer than 25. The eldest nuns are more active than they should be. They seem tired. Everyone has a ministry, everyone has a chore. With some of them approaching or past the age of 80, watching them work is like watching your elderly grandmother do things you wish she wouldn’t: uncomfortable. The other night one sister sat down breathlessly and popped what I assume was a nitrate pill. Within minutes, she saw something that needed doing and back sprang up. She wouldn’t let anyone help her.

“Oh, I’m ok now,” she told said. “I’ll just have to deal with the headache from this pill.”

The nuns here follow a Monastic schedule. Mondays through Fridays they assemble in the cafeteria for silent breakfast at 7:30 am (I’m so proud that I’ve remembered not to speak), then for Morning Praise at 8:30, 11:30 for the Eucharist (and on Tuesday’s only at 11:40 for Mid-Day Praise), at 12:10 for dinner (not supper, I was told), at 5:00 for Evening Praise, and at 5:30 for supper. After supper I join my “dark dish” washing partner (the term has nothing to do with spiritual things but refers to the color of the pots and pans) and several others in one of the fourth floor TV rooms for world news. The TV is usually turned off afterwards. Then the sisters and I get off the low-slung sofas in the TV room and go to our rooms, me to write, them to do I don’t know what. Very few of them take the stairs.

As I got off the elevator this morning, I chanted “Harry W. Morrison, Harry W. Morrison,” so I wouldn’t forget and made a beeline for my laptop. Who was he, I wondered, and why did he care about nuns in Cottonwood, Idaho?

I soon read that Harry Morrison came as a young man to Idaho from Illinois to work in construction. In 1912, he and Morris Knudsen started Morrison-Knudsen, a construction business. Fortunately for the sisters here (and many other beneficiaries elsewhere) he believed that to be worth one’s salt, a man had to make the lives of others better. The philanthropic foundation he started in 1952 with his first wife that now bears his name, the Harry W. Morrison Foundation, was his tool to do that. The Foundation’s website says about him:

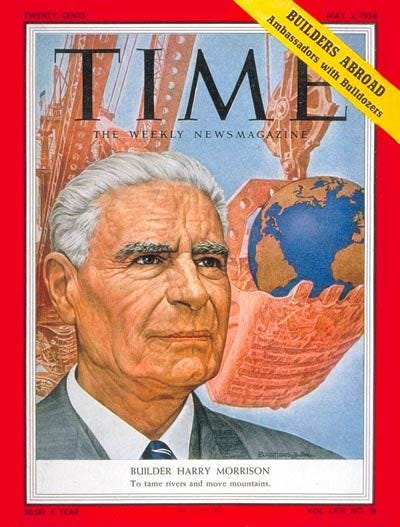

“Morrison-Knudsen went on to build big things: dams bridges, tunnels, railroads, highways, pipelines, airports, military bases, space centers—an astounding inventory of structures on every continent of the globe. Admirals, kings, shahs, presidents, and business leaders all over the world trusted him to handle the largest, the most sensitive, and the most challenging construction jobs the world had ever seen. Mr. Morrison's many construction achievements garnered him the Time Magazine cover on May 3, 1954. They called him "the man who had done more than anyone else to change the face of the earth."

According to the Foundation, Harry and Ann started the foundation “as a means of supporting educational and charitable institutions. Funds went to churches and college buildings, scout camps, and to a wide variety of other community programs, mostly in Idaho, their home.”

But that was only part of the story. After I posted this today, I learned it was actually his second wife Velma (who he married after Ann passed away) who was responsible for the elevator. Somehow she learned that St. Gertrude’s previous elevator was trapping nuns inside. Because she had been trapped in an elevator once, she arranged for St. Gertrude’s to get a new elevator: the one I take up and down several times a day. She just didn’t get her name on the brass plate.

The nuns are appreciative, but today the sisters cautioned me to be careful in her elevator. It was installed 15 years ago and has been known to trap people now although they say it usually gives advance warning by acting up. Soon the sisters will begin raising money for a new one. All you well-heeled people out there want to lend a hand?

Regardless, I'm just glad I don't have to climb stairs and stand by my earlier blessing, only adding one thing to it: Velma. Harry may have been worth his salt, but so was she.

And just one more thing. Tonight the elevator is acting up.